Nine words was all it took to change my life. Nine words that drew a ruler straight line between the bright world of before and the uncertainty of after. Nine words spoken by a French Doctor moments after I had been ejected from a CT scanner.

“Do not move. Very Dangerous. You’ve broken your neck.”

I should provide some context…

In the 14 years since I broke my neck, the question I have been asked more than any other, is how did I do it? And in almost every case, I have skirted around the truth. I tell people ‘I was away snowboarding.’ And that is true – I was indeed away snowboarding. If they push for more information, I tell them ‘I went over a great big jump’. And again, this is true, I did indeed go over a great big jump. But there is a lot I am leaving out from those two answers…

It was the last night of the holiday and our group of twenty friends was about to make a decisive split: those who wanted to go to the pub and the those who wanted to stay in the chalet. In a rare moment of self-restraint, mainly driven by my desire to have at least one hangover free day of snowboarding, I surprised myself by opting to join the half that were staying in. Less than thirty minutes later, our resolve was crumbling. The opportunity for one last night of excitement was tugging at everyone’s distracted thoughts. But then my wife had an idea. An idea that, myself included, we all thought was brilliant.

‘Let’s go sledging,’ she said.

And that’s how twenty minutes later I found myself next to my friend Bryan, skooched onto my snowboard, sitting on top of a twenty foot jump that led down to our chalet. The sledging had been a gentle pootle around the nursery slopes until Bryan had spotted the jumps. To my optimistic eyes they didn’t seem steep, a gradual incline up to a flat area at the top and an equal slide down the other.

‘We should aim for the first snow ramp and go over that on the way down,’ I said, pointing towards the other snow ramp that was just a grey hump about a hundred metres in front of us. Bryan looked sceptical. ‘Are you sure we won’t be going too fast?’ he asked.

I am not entirely sure why Bryan thought I would be the knowledgeable voice of reason in relation to sledge velocity and speed, but I was seconds away from spectacularly demonstrating that I was not the right person to answer that question.

‘Nah, it’ll be fine. I don’t even know if we’ll get enough speed up to reach it, never mind make it over.’ And right there, seconds after uttering the most idiotically incorrect sentence of my life, is where my recollection of that night ends. I have nothing, absolute, total darkness.

This is what I was told…

We set off and it was immediately apparent that we were building up more speed than either of us had thought possible. Bryan, being either brave or incredibly stupid, maintained his course and hit the ramp straight on. Up one side, he was catapulted from the top and thrown down the slope. He was lucky. The gradual incline ensured that his fall was not too bad: a broken wrist and a bloody nose. I wasn’t so lucky. At some point coming down the hill, I must have realised that this was not a good idea.

Taking what I like to think was a more sensible approach to Bryan’s confident leap, I decided to avoid the ramp. Too late, though. I veered to the left but continued upwards. Instead of going straight over the side with a gradual incline, I launched off the left-hand side and was hurled thirty, maybe forty feet into the air. Some years later, when we were able to look back on the accident through a different lens, my wife joked about how my arms flapped desperately as I flew through the air, some primal desire to fly my way out of trouble surging through my body and mind. I didn’t fly, though. Quite the opposite, I crashed to the ground in a shattered and unconscious heap.

I had broken my neck, the second verterbra (C2) in multiple places and would require a variety of neck braces for over a year. To add insult to the literal injury, I had also broken my pelvis in two places, my hip, and my wrist.

In the 14 years since I broke my neck, the second question I have been asked more than any other, is whether the accident changed my life. And for a long time, I thought the answer to that question was no. I saw no defining or lasting difference beyond the physical limitations. But a lot has changed for me in the last few years. And as I look back on the months and years since the accident, I have a new understanding and perspective about my outlook on life.

I remember the day, mere weeks after the accident, where I wheeled myself up to my dining room table for conference call with Hewlett Packard. Working for a small consultancy company meant that there was only one option open for me if I wanted any financial security through my recovery: I had to work. That’s how I found myself pitching to Hewlett Packard for a six month project that I could deliver from home. Long before the invention of Zoom, I was glad that they couldn’t see my shattered body as I told them my injuries were minor and that I could absolutely do the job. That twenty minute call left me exhausted and sweating. But we won the work. I delivered on time and it gave me focus and purpose throughout my recovery.

I remember the day, excited and happy about progressing from my wheelchair to a Zimmer frame, that I walked to the corner shop to buy a loaf of bread. The usual two-minute walk took me just under an hour. But I held that loaf of bread aloft like it was the World Cup Trophy when I got home.

I remember the long nights. Alone with my thoughts. Unsure of my future.

I remember returning to work. A week away in Bracknell. Still wearing my neck brace and utterly exhausted, I stared at the train doors that were the first step on a four hour journey home. The doors opened and I had an abrupt and terrifying realisation. I could not lift my bag. Physically and mentally I was broken and the thought of the journey I needed to take was impossible and overwhelming. And then someone stepped forward. And I watched in awe as stranger after stranger helped me from Bracknell to Reading, to Paddington, to Liverpool Street and then finally, onto my train home.

I remember a moment of hope. Months after the accident it was the first time I was able to briefly remove my neck brace. Tentative and terrified I released my fragile neck and stepped into the shower. A stream of water flowed over my body and washed away so much more than the months of dirt that had accumulated. Ten minutes. Ten minutes without the constraint of my brace. Ten minutes where I felt the first optimistic dawn of a new and different future.

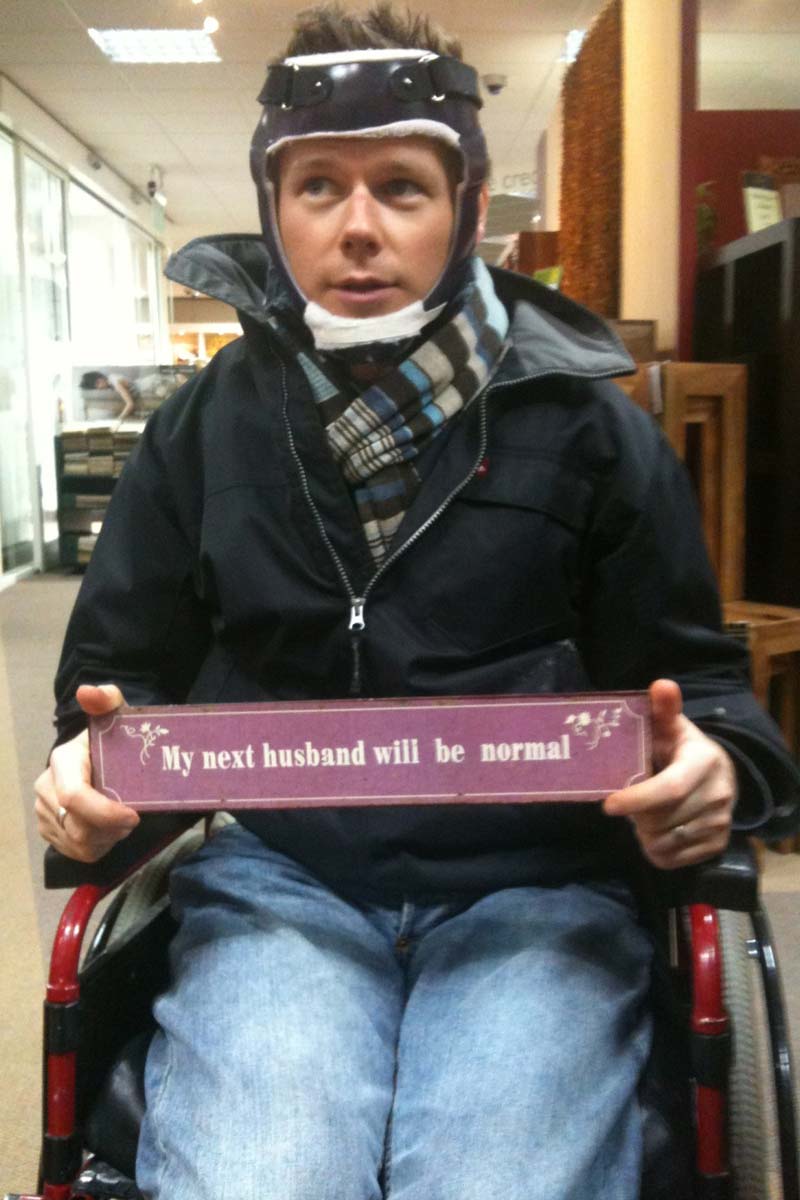

I remember laughing with my wife as she asked me to hold a sign we find whilst shopping…

Breaking my neck may have been the catalyst. But it was these moments that truly changed my life. The struggles. The fear. The laughter. The micro-moments of success. The setbacks. The support and kindness of others. These challenges have shaped the person I am. And in every possible way, they have made me a better person. A stronger person. A more resilient person. A more appreciative person.

So wherever you are. Whatever you are going through right now. However hard it may seem. I want to leave you with nine words. Nine words to remember. Nine words to guide you through the difficult times. Nine words that might just change your life…

“Never forget. What doesn’t kill you…makes you stronger.”